In 2010 tens of millions of Americans will be switching to dishwasher detergents that are phosphate-free. Soon your life will be changed in this small but important way by a Sierra Club volunteer, Rico Reed, and the Sierra Club’s Spokane River Project.

The impact on America’s waterways will be almost immediate - improved water quality and aquatic health. And because less phosphate will be entering the nation’s wastewater stream, treatment plants must remove less - saving taxpayers billions of dollars.

In the spring of 2004 Rico Reed, who chaired the Political Committee of the Sierra Club’s Spokane-based Upper Columbia River Group, picked up a box of dishwasher detergent, read the label, and discovered phosphates were inside. Reed, working with Sierra Club lobbyist Craig Engelking in Olympia, and Rep. Timm Ormsby, took the first steps that led to Washington’s law banning phosphates from dishwasher detergents to protect waterways.

In 2008 Spokane County implemented the first-in-the-nation ban - with a nearly 10 percent drop in phosphates entering the City of Spokane’s water treatment plant. Here is Rico’s story.

John Osborn: How did you first become involved with phosphates in dishwasher detergents?

Rico Reed: My general approach to a safer environment is to first stop adding to the problem. It’s like the doctors’ oath: first, do not harm.

Up until we moved to a house with a dishwasher, I washed dishes by hand. While shopping for a dishwasher detergent in 2004, I was surprised to discover phosphates in the ingredients. I really thought we had already eliminated them when Washington state eliminated phosphates from laundry detergent back in the 1990s.

I started investigating whether eliminating phosphates from dishwasher detergents would make a difference for water quality. I spoke with the chemist at the Spokane Wastewater Treatment Plant who provided a range that dishwasher detergents contribute to total phosphates entering the treatment plant. He estimated about 6-12 percent – and it turns out he was pretty close. And then I spoke to Rachael [Osborn, Sierra Club’s Spokane River Project coordinator] who said, “Yes, sounds like a good idea. If you want it done, then you need to take the lead.” So I said, yes I’ll do it.

I did a little write up and took it around to all of the legislators and talked with all who would take the time. In Washington the legislature meets starting in January for 60 or 90 days depending on the year. That meant winter driving for 300 miles over a mountain pass to prod people who I knew were mostly having more contact with the industry lobbyists outside of normal hours.

JO: They knew who you were?

RR: Because of my political activity through Sierra Club and some from my run for state rep. in '92.

They all spoke agreeably about the issue, as politicians almost always do when you talk with them. But they didn’t have the time -- until I got the newest representative, Timm Ormsby and his aide Richard. Timm said it was too late to have any expectation to pass a bill during the 2005 session. He would try to get it in the hopper for the session the following year.

JO: And the following year found you contending with the industrial lobby?

RR: The soap lobbyists talked about test marketing a phosphate-free product in Arizona and consumers complained. That was proof enough for them that it couldn’t be done. The industry also did not speak with one voice: many small independent companies were already selling a phosphate-free product.

The soap lobby argued that it would cost consumers more. And in some cases the new products did cost more, but not all. But when you factored in the cost of upgrading or building new sewage treatment plant, the cost on the grocery shelf was minuscule.

Companies and municipalities with permits to discharge waste-water to the Spokane River were supportive of what we doing – they knew that phosphates levels had to drop in order to meet the water quality standards under the federal Clean Water Act. Preventing phosphorus from entering the wastewater system was an easy and inexpensive way to treat the problem – and also reduce the dischargers’ need to act to address their own impacts.

JO: The soap lobby argued that no other state had passed a ban, as a reason that Washington state shouldn’t either. And then came the 2006 legislative session.

RR: Yes, Rachael and I testified – as well as Sierra Club volunteers from the Cascade Chapter. The Soap and Suds lobby vigorously opposed us, saying there was no satisfactory substitute for phosphate. We countered with arguments that several 100% phosphate-free products were on the market, that did a fine job. One of the companies, 7th Generation, sent their representative Martin Wolf. He testified that 7th Generation has a good product -- and enough to supply the entire state. The Legislature did not need to worry about clean dishes in Washington.

During the legislative battle we had help from our regional utility, Avista Corporation, potentially on the hook for water pollution problems behind its dams. We also had help from elected officials, including at least one county commissioner who wanted to make sure that development didn’t stop because of river pollution. This commissioner, Todd Mielke, became very well informed and was a much better public speaker than I, even though his motive was much different than mine.

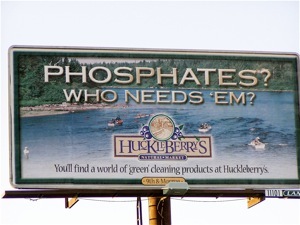

During the legislative battles local stores in Spokane advertised phosphate-free detergent - years before the big box stores.

In the Legislature the soap lobby worked to kill our bill, and then to try and reduce the number of counties that the law would apply to, and wanted 10 years more before implementing the ban.

JO: When the bill passed and was signed into law, what was your response?

RR: I was disappointed that the ban wasn’t statewide and immediate. I knew that alternative product was available, and that there was an immediate threat to the waters of the state. But I was also politically conscious enough to know that that was the way things are done.

JO: And more challenges were ahead?

RR: Yes, the soap industry insisted that they couldn’t market their phosphate-free product in 2007. Two of four counties were asked to be let out of the initial phase-in. The lobby also succeeded in amending the law to delay implementation for another year.

JO: How does the ban in phosphates in dishwasher detergent connect to laundry detergents?

RR: Spokane County also led the nation in reducing phosphates in laundry detergents. Lake Spokane [the reservoir formed by one of Avista’s dams] had a particular problem with algae blooms. Any algae in large concentrations can be a problem for cold water predator fish such as trout because, as the old algae dies it settles to the bottom, and in the process of rotting it consumes so much of the oxygen that the fish will die when the upper waters are too warm for them to seek oxygen there. There are also some species of blue-green algae that produce toxic blooms in warm water. In 1990, after cattle died from drinking Lake Spokane water during an algae bloom, Spokane County public health officials ordered a ban on phosphates in laundry detergents. The ban went statewide in 1994. It was that ban that I had assumed extended to dishwasher detergents.

JO: In July 2008 the ban on phosphates in dishwashing detergents went into effect in Spokane County – the first in the nation.

RR: Some of the stores were without any dishwasher detergent for awhile. They didn’t plan ahead. I talked with a Costco manager a couple of times before the ban but they still failed to get their manufacturer to change. Costco pulled their own product off the shelves and at first had no dishwasher detergent then a couple weeks later they had the specialty manufacturers’ products. WalMart was one of the first that had a big-name brand that was phosphate-free.

JO: What about “soap smugglers”?

RR: We also had to contend with the “soap smuggler” stories in the LA Times and the Associated Press – how people were traveling from Spokane to Idaho to “smuggle” their favorite dishwasher detergent back to Washington. It says more about people’s unwillingness to change and look at new options than it does about what is available. Some of the phosphate-free products worked better than others, and people didn’t have information to make the best choices. And the products weren't as available as they are now. The soap smuggler stories came off ridiculing the people of Spokane, or in some talk shows as government invasion into private choice. The real story was government taking steps to prevent the poisoning of the public’s waters from toxic algae blooms.

JO: Is the “ban” 100 percent on phosphates in dishwasher detergents?

RR: No, one-half a percent is allowed – so that the manufacturers don’t have to measure trace amounts that may be contaminating their product. Pre-ban percentages ranged from 4 to 10 percent phosphate.

JO: What have been the impacts?

RR: When the County’s ban on phosphates in laundry detergent went into effect, the Spokane Wastewater Treatment Plant noted a drop in incoming phosphates of 20%. With the ban on dishwasher detergent, the water treatment plant is reporting substantial declines of incoming phosphates; as much as 10%. The cost of technology upgrades to remove phosphates will be high. Preventing phosphates from entering the system is cheap.

JO: So this is “low hanging fruit” among the remedies for cleaning up our waters – this is an easy solution?

RR: Yes, phosphates are extremely expensive to remove once they're in the system, and the older sewage treatment technologies don’t remove any.

JO: For citizens who care about the environment, what are the take-home lessons?

RR: I had to be persistent and make a lot of visits with elected officials before I found one person who would sponsor a bill. I thought it was such a logical thing to do, that once introduced it would be a shoo-in -- but it still took a lot of lobbying to get it passed. The newest legislative member, Rep. Timm Ormsby, found time to work with us on the bill. He wasn’t already part of the system, and it might be just that he was a great guy.

The legislative change is a slow process, and you had better be prepared to be persistent. Bills live or die for totally illogical reasons – at least to an outsider. That’s where Craig Engelking (Sierra Club’s Olympia lobbyist in 2006) was really helpful to me in understanding the internal workings of the Legislature. The fix to this water pollution problem seemed so obvious you’d think everyone would have embraced it. But it always takes more than you’d expect.

Rico and his wife, Myrna have since relocated to Hakalau, Hawaii, where they once again don’t have a dishwasher. 15 states will be implementing phosphate bans in dishwasher detergents in 2010.